Status

Genres

Publication

Description

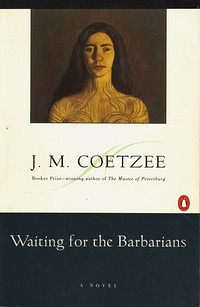

A modern classic by Nobel Laureate J.M. Coetzee. His latest novel, The Schooldays of Jesus, is now available from Viking. Late Essays: 2006-2016 will be available January 2018. For decades the Magistrate has been a loyal servant of the Empire, running the affairs of a tiny frontier settlement and ignoring the impending war with the barbarians. When interrogation experts arrive, however, he witnesses the Empire's cruel and unjust treatment of prisoners of war. Jolted into sympathy for their victims, he commits a quixotic act of rebellion that brands him an enemy of the state. J. M. Coetzee's prize-winning novel is a startling allegory of the war between opressor and opressed. The Magistrate is not simply a man living through a crisis of conscience in an obscure place in remote × his situation is that of all men living in unbearable complicity with regimes that ignore justice and decency. Mark Rylance (Wolf Hall, Bridge of Spies), Ciro Guerra and producer Michael Fitzgerald are teaming up to to bring J.M. Coetzee's Waiting for the Barbarians to the big screen.… (more)

Media reviews

User reviews

The civilized person in this novel is the Magistrate of a border town/garrison, somewhere on the frontier of an unnamed Empire. Tima and place are unspecific in an historical context, though Coetzee creates a powerful and beautiful image of a remote near- desert landscape, where the seasons come and go in passages of extraordinary beauty. The Magistrate's peace -- and the town's -- is shattered with the arrival of a senior intelligence officer, who starts rounding up prisoners from outside the walls as sources of information on the massive barbarian attack he (and his Empire) expect (or say they expect). The Magistrate tries to first to prevent the torture of the prisoners, and then to ignore it, but cannot distance himself as he would wish.

Other reviews outline the story; suffice it to say that the Magistrate progresses from pained acquiescence to the actions of the intelligence officer, through an off-focus love affair with a barbarian girl. to eventual imprisonment as a traitor, to eventual defiance, to total humilation, and finally back to a magistrate's role -- but the magistrate of a town that is "Waiting for the Barbarians".

This book operates on all kinds of levels -- political, personal, and aesthetic -- and never reaches any definitive conclusions. But for me at least it is extraordinarily powerful, and very beautiful.

Unlike some readers, I didn't find it oppressively negative. It does take a grim view of some elements of human nature (particularly the nature of power) but it does not present those as the only way that people can be. Tragic, perhaps, rather than oppressively negative.

The magistrate of a small outpost in an unnamed empire is quite

So, the question is: just who are the barbarians in this story? Is it the nomadic people who just seem to want to live life as they always have? Or is it the "civilized" people from the empire who torture, kill, maim, lie, cheat, rape etc.? The parallels between this story and the European treatment of aboriginals whether in North America, or in Australia or Africa are obvious. My feeling is that the barbarians are all around us. Some people are worse and some people are better. The magistrate in this book at least had a conscience and thought about his role. After reading this book I think I now believe that Coetzee has a conscience, which is more than I would have given him credit for after reading Disgrace.

This following passage was one that resonated with me:

I think of a young peasant who was once brought before me in the days when I had jurisdiction over the garrison. He had been committed to the army for three years by a magistrate in a far-off town for stealing chickens. After a month here he tried to desert. He was caught and brought before me. He wanted to see his mother and his sisters again, he said. "We cannot just do as we wish," I lectured him. "We are all subject to the law, which is greater than any of us. The magistrate who sent you here, I myself, you--we are all subject to the law." He looked at me with dull eyes, waiting to hear the punishment, his two stolid escorts behind him, his hands manacled behind his back. "You feel that it is unjust, I know, that you should be punished for having the feelings of a good son. You think you know what is just and what is not. I understand. We all think we know." I had no doubt, myself, then that at each moment each one of us, man, woman, child, perhaps even the poor old horse turning the mill-wheel, knew what was just: all creatures come into the world bringing with them the memory of justice. "But we live in a world of laws," I said to my poor prisoner, "a world of the second-best. There is nothing we can do about that. We are fallen creatures. All we can do is to uphold the laws, all of us without allowing the memory of justice to fade." After lecturing him I sentenced him. He accepted the sentence without murmur and his escort marched him away. I remember the uneasy shame I felt on days like that. I would leave the courtroom and return to my apartment and sit in the rocking-chair in the dark all evening, without appetite, until it was time to go to bed. (p. 136)

When I was attending law school I took jurisprudence which is the study of the philosophy of law and the question of what is justice is one that we discussed frequently. Laws are not always just. In fact, depending on your position and point of view, they are often not just. I don't know that I believe we can only uphold the laws. Sometimes I think we have to challenge them. But certainly we can't allow "the memory of justice to fade".

Set against the (necessary) paranoia and deafness of empire, “Waiting for the Barbarians” inhabits the balanced and reflective perspective of an amicable boondocks magistrate who finds his duties growing morally questionable just when they should be at their automatic, pre-retirement best. He’s the nice-guy-who-didn’t-really-want-to-have-to-accept-his-complicity-with-the-atrocities-committed-on-the-periphery-of-empire, the guy who is almost remorseful that he can’t quite turn a blind eye to torture and arbitrary imprisonment . . . oh wait . . . that’s right, unless you are currently some sort of progressive activist or a waterboarding cog, he is supposed to represent you! And what do you need to know? Well, unless you are a television-fed collision monkey, nothing, probably, and Cotezee doesn’t motivate with his writings; he just sort of lays it out there, where you knew it was.

His treatment of permanence, of marking, of spoiling and claiming, losing and being forgotten, is multi-layered and well integrated into the love relationships of the book. However, the interplay of these themes would have been more rewarding if the narrator did not signpost and dissect each area of overlap.

A few examples of the endearing narrative deadpan: addressing his cock, “Why do I have to carry you about from woman to woman, I asked: simply because you were born without legs? Would it make any difference to you if you were rotted in a cat or a dog instead of in me?”

“They are tearing down the houses built against the south wall of the barracks, he tells me: they are going to extend the barracks and build proper cells. ‘Ah yes,’ I say; ‘time for the black flower of civilization to bloom.’ He does not understand.”

And then an example of the more pedantic and obvious, “Empire dooms itself to live in history and plot against history. One thought alone preoccupies the submerged mind of Empire: how not to end, how not to die, how to prolong its era. By day it pursues its enemies. It is cunning and ruthless, it sends it bloodhounds everywhere. By night it feeds on images of disaster: the sack of cities, the rape of populations, pyramids of bones, acres of desolation. A mad vision yet a virulent one.”

The novel operates capably along this spectrum.

A book I am going to buy and slowly examine at a later time. Such a lot to learn from an otherwise unimposing volume.

Excellent book too, so long as you don't mind grim. That said, it is uplifting in a curious way, detailing the ability of the human spirit to survive in the face of the most extreme tortures. You have to get over your distaste for the narrator's relationship with the young girl too - standard Coetzee stuff, though the more I read him the more I think, yeah, he's got a point actually, I don't dislike this because he's chosen to create some fantasy old-perv/ young girl relationship, but because such relationship are all to real (imagined or otherwise) and still highly dislikeable. We are dislikeable creatures. Us men. Isn't that his point?

P.S. Expect many unsavory sex-like acts. Nearly half the book is devoted to such topics. Not exactly graphic, but definitely icky (to me anyway).

• I had a hard time getting into this book. This is the third time I have tried to read Coetzee and have concluded that his writing style just does not appeal to me.

• I also think that this book might have had a greater impact or resounded with me better if I had read it when it was

• It showed the physical abuse/torture as a way to break the spirit and mind. Also thought that this helped to show while others who were part of the oppressor class/race that did not agree with the handling/treatment of the “barbarians”/oppressed would hesitate to speak out or help the oppressed. And how the oppressor controlled the messages about the oppressed.

• There was not much emotional connection for me with this book – I was surprised because of the subject matter.

I wish I could say this was a four star book, but I really wasn't satisfied with the way that the plot turned in the last third of the book. I thought that toward the end of the book the central character lost a great deal of his "autonomy" and became more and more of a "vehicle" for the author. Since the author is J. M. Coetzee, it is interesting to see how this plays out, but I have a preference for fictions where there is less sense of a puppetmaster manipulating plots and thoughts in order to make a point, however valid that point might be.

This is a story within a fictional empire that exists in a timeless, somewhat feral world. This Empire centres around the trade of provisions and the protection against attacks from the Barbarians who live on the outskirts of the Empire. The

The magistrate, for unknown reasons, attempts to bond with the girl in a ritual that is almost but not quite romantic. He then sets out to return the girl to her tribe, and subsequently suffers an accusation of treason by the colonel. Armies who have arrived to destroy the Barbarians take him prisoner. His own subsequent degradation and torture makes him a sort of fallen hero, one that forces him to examine how and why he is willing to suffer for what he believes in, as confused as it may or may not be.

It’s not out of step as far as Coetzee novels go, in their spare, descriptive exploration of degradation and redemption.

Anyway, everyone should read this book. It's not that subtle, but none of his books are, and it's not quite as offensively blatant as Foe. It'll take you three hours to read, tops. Go for it.

The primary details of the story center on the relationship between the Magistrate and a young blind girl, a barbarian who begs for to survive. The Magistrate takes her in and the relationship that develops between them mirrors the growing dissatisfaction of the Magistrate with the Empire. He eventually takes action that will have significant consequences for his life, leading to lessons about freedom, justice, and the meaning of life within the Empire. The climax of the novel is powerful in the sense that principles are powerful in the lives of humans. The allegory is effective and the story is masterful. It is not surprising that Coetzee won the Booker Prize for this novel.

“is a distinguished piece of fiction, and what Mr. Coetzee has gained from his strategy of creating an imaginary Empire is clear. But are there perhaps losses too? One possible loss is the bite and pain, the urgency that a specified historical place and time may provide. To create a 'universalized' Empire is to court the risk…that a narrative with strong political and social references will be ‘elevated’ into sterile ruminations about the human condition. As if to make clear what I'm getting at, Mr. Coetzee's American publishers quote from a London review of the novel by Bernard Levin: ‘Mr. Coetzee sees the heart of darkness in all societies, and gradually it becomes clear that he is not dealing in politics at all, but inquiring into the nature of the beast that lurks within each of us....' That ‘a heart of darkness’ is present in all societies and a beast ‘lurks within each one of us’ may well be true. But such invocations of universal evil can deflect attention from the particular and at least partly remediable social wrongs Mr. Coetzee portrays. Not only deflect attention, but encourage readers, as they search for their inner beasts, to a mood of conservative acquiescence and social passivity.”

The main theme is that of Empire. Maintaining the power of Empire, which requires the "othering" of those not of the Empire. In the small town on

One day representatives from the Empire (and the only characters who are given names) arrive. Rumors have swirled around about the impending attack from the Barbarians, and these representatives are sent to protect the village.

Torture ensues, executions, death, the Barbarians are "swept away" leaving one young woman who remains behind begging for scraps. The Magistrate, of course, is witness to the inhumane treatment of these people and takes the woman in. Their relationship is one of the oddest I've ever read.

He spends a lot of time massaging her with oils, paying particular attention to her broken ankles and bruises. They sleep together, but there is no sex. For that he visits one of the many girls upstairs. For about 50 pages, the man has an existential crises with his penis. Why does it work for his girl upstairs but not for the girl in his bed? Why is he comfortable stroking her but not sexually? (I don't know, maybe because she is the "other?")

Eventually, the Magistrate takes the girl back to her people. It is a long journey during which horses die, guards become surly, and they all stink to high heaven because they haven't bathed. (Coetzee spends a lot of time describing the foulness a body experiences when one is not allowed to bathe.)

This journey gets the Magistrate into terrible trouble, and he soon becomes "other." Arrested, tortured, neglected, the Magistrate reflects on what has become of him and understands that the mythical Empire has become the very barbarians being warned of.

Descriptions of torture made me gasp. The creativity, the brutality. I don't wan to know if these methods have really been used or are the product of Coetzee's imagination. They drive home the point that while demonstrating to its own population what being other means, an empire becomes other itself.

Shades of Orwell and Kafka lurk in the shadows of Waiting for the Barbarians. It is not an easy book to read.